Powell’s Essential List: 25 Best Sci-Fi and Fantasy Books of the 21st Century (So Far)

50 Essential Science Fiction Novels (Part 2: 1979 - 2011)

29. Raymond Briggs' When the Wind Blows (1982). With apologies to Pat Frank's Alas, Babylon, Nevil Shute's On the Beach and Simon Morden's Thy Kingdom Come, I think this slim and poignant graphic novel makes the most essential of the essential post-nuclear reads. In a few short (and beautifully illustrated) pages, Mr. Briggs brings home the real horrors of the apocalypse.

28. Julian May's The Saga of the Exiles (1981 - 1984). Sadly, not every selection can possess the same level of literary significance as The Brave Little Toaster. But The Saga of the Exiles is a sterling example of the Vast SF Epic. In a semi-utopian future, the malcontents and misfits throw themselves through a portal to Earth's distant past. There they find that they have company: two disgruntled species of aliens. The four book series juggles politics, adventure, psychic battles and a quest or two. A great example of SF as entertainment - made more so by the complex plot and well-developed characters.

27. Thomas Disch's The Brave Little Toaster (1980). Yes, it is about a toaster. And yes, it became a (amazeballs) movie with songs about trash compactors . But also, yes, it is science fiction that's about our relationship with inanimate objects and the stuffs of life. It is about the balance between progress and nostalgic, the tension between "owner" and "owned", loyalty and slavery and, to no small degree, robots and machine sentience. Also, this song is awesome.

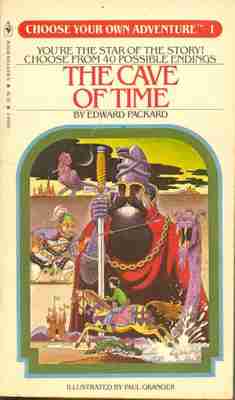

26. Edward Packard's The Cave of Time (Choose Your Own Adventure #1) (1979). How convenient that the first of this series is a time travel adventure, but, really, The Cave of Time is just the token representative of this franchise's insane significance in indoctrinating the youf of many generations into science fictional narratives.

30. Tim Powers' The Anubis Gates (1983). One of the most cleverly-crafted time travel novels and also a sterling representative of steampunk's literary side, in which the values and history of the 19th century is inextricably woven throughout the book.

31. William Gibson Neuromancer (1984). Just as compelling and prescient now as it was in 1984. The technology feels a bit clunky and dated, but tech-based SF does get... clunky and dated. Neuromancer succeeds where many of its cyberpunk peers fail because it isn't reliant on the 'cyber' - the novel focuses on the revolutionary relationship of Case and Molly to the system that created them.

32. Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale (1985). Yup.

33. Orson Scott Card's Ender's Game (1985). This is a problematic book from an author with deeply problematic views, and, I put it on here despite every possible reason to avoid it. Ender's Game is an amazing book that touches on eugenics, child soldiers, the nuclear family, the dehumanising of the soldier and the intangible, psychological horrors of war. It also has the Battle School fights, which are like the great SF 'sports story' ever told. (I'd argue that even Mr. Card doesn't know how he got Ender's Game right, as evidenced by the endless sequels, prequels and re-quels that have followed.) Buy it used.

34. Haruki Murakami's Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (1985). Speaking of psychological horrors, this novel - one of Murakami's best - probes inside the layers and layers and layers of the human mind. A genre-bending, indescribable masterpiece that feels a bit like Slaughterhouse V, a bit like Chandler and mostly something completely unique.

35. Alan Moore's Watchmen (1986). Superheroes are arguably science fictional, but this is also a stunning alternate history and one of the best SF Cold War narratives. Mr. Moore's argument against the filming of his work has always been that he writes stories bespoke to their media - and it is hard to argue against the ultimate superhero narrative existing as anything besides a comic book.

36. Pat Cadigan's Mindplayers (1987). Extremely dense and wonderfully trippy, but the style of Mindplayers matches its substance. In a future where psychosis comes in pill form, this book explores the results and repercussions of a free-wheeling existence where perception is both unreliable and mutable. It is a concept that simply wouldn't work in the hands of a lesser writer, but Ms. Cadigan gets the reader into Ally (the protagonist's) head.

37. Warhammer 40,000 (1987). "In the grim darkness of the far future, there is only war..." If Dungeons & Dragons is inextricably linked to the creation of modern fantasy (and it is), only one science fiction game can boast the same level sort of reach. A quick flick through the basic manual shows why - this is a future unlike any other, a hideous, eternal conflict that pits the hideous against the horrific. As a tabletop game, 40k also brings with it a different philosophy from that of the conventional heroic narrative: there are no absolutes, only factions, each convinced of their own right. Dismiss this as 'toy soldiers' at your own peril, no other book on this list has had as much direct influence on modern science fiction.

38. Iain Banks' The Player of Games (1988). There are, arguably, layers of meaning to Mr. Banks' space operas - cultural perspective and technology and stuff. I'm not wholly convinced. Nor do I need to be - Mr. Banks is one of the great storytellers of the genre, and The Player of Games, the most epic battle of boardgames since Death played chess, is one of the best of its class.

39. Michael Crichton's Jurassic Park (1990). Touchscreen computers, Chaos Theory, gene tampering, evil billionaires and velociraptors. What's not to love? Twenty years later, still the great SF thriller, in the way that it blends together action, heroism, 'plausible' science and mystery.

40. Richard Russo's Destroying Angel (1992). Three cyberpunk novels deemed 'essential' is probably excessive, but, unlike Mindplayers and Neuromancer, Richard Russo's bleak vision of near-future San Francisco also crosses over into noir. There's a mystery and some cyberpseudosciencehandwaviness, but the first Carlucci story is mostly about a battle for souls - bottomed-out players (good and evil) trying to crawl towards their particular light.

41. Nancy Kress' Beggars in Spain (1993). A single speculative twist - a gene that removes the need to sleep - exploded out over the course of a novel. The science is silly (and gets progressively sillier), but Ms. Kress looks into the social consequences of the haves/have-nots (Sleepers and Sleepless) and doesn't hesitate to discuss the ethics of being "chosen".

42. Simon Green's Deathstalker (1995). The largest, most outlandish space opera concievable as a motley group of superhumans find bigger and bigger guns (and fire them). The series goes on endlessly, with the guns getting ever bigger and the plot twists ever sillier. But Deathstalker is one link in a long chain of shamelessly escapist SF that goes back to Burroughs and Brackett and will go forward until the end of time. It is essential because it can't be ignored... and I really enjoy it.

43. Koushun Takami's Battle Royale (1999). Arguably, this position belongs to Suzanne Collins' The Hunger Games (2008), but, in this case, talent (and precedence) supersede scale. Battle Royale is the gut-churning story of a dystopian future in which schoolkids fight to the death. Whereas Collins tries to mitigate the horror by keeping her heroine free of moral ambiguity, Battle Royale is relentless in picturing the depths to which "innocents" can fall. And it is all the more effective for it.

44. China Miéville's Perdido Street Station (2000). Another author I'd like to have on twice. The City & The City is simply astounding, but, in this case, I think the way that Perdido talks specifically about science - its repercussions, ethics, commitments & demands - makes it more relevant to a list of essential science fiction. Plus, like all of Mr. Miéville's works, there's a heady political subtext in here about freedom, revolution and the rights of the individual vs those of the state.

45. Tricia Sullivan's Maul (2003). Two futures - one real, one virtual. Two middle-class teenage girls try to survive them both. A plague has wiped out men, leaving the survivors as objects, not agents. Meanwhile, ambitious women use clones and children as currency, and there's a wild splatterpunk anti-commercial streak that not only links the whole thing together, but makes it surprisingly fun. Described as post-cyberpunk, post-feminist, post-apocalyptic... Maul has posted itself way out there on its own.

46. Sophia McDougall's Romanitas (2005 - 2011). A stunning example of a modern alternate history, as the series doesn't get distracted by the 'big idea' of the setting. (Compared to, say De Camp's time travel novel, Lest Darkness Fall (1955) which is a) racist and b) all ZOMG ROMANZ!) Romanitas and its two sequels written in a way to parallel their years of release in the real (er, our) world. Ms. McDougall doesn't shy from discussing the tricky issues of both times - so the novels touch on terrorism as much as they do slavery. They're also brilliantly character-driven and filled with unexpected, but oh-so-right plot twists. (Another series hotly contesting this particular spot: Jon Courtenay Grimwood's Arabesk).

47. Nick Mamatas' Under My Roof (2007). Judging books from the past five years is tricky, but Under My Roof, a little-known satire by Mr. Mamatas, encapsulates a whole sub-sub-genre of wry, ostensibly young adult satire. Herbert Weinberg's father builds a nuclear bomb and Weinbergia (his house) secedes from the rest of the United States. His actions, as viewed through the eyes of his (telepathic) son, have unintended consequences, and, before long, Herbert is seeing the entire world change.

48. Jonathan Green's Leviathan Rising (2008). If half of steampunk is in the tradition of The Anubis Gates, the other half is well-represented by Mr. Green's long-running Pax Britannia series. It is pure, wonderful pulp thinly veiled behind the Victorian aesthetic. In this volume, special agent Ulysses Quicksilver battles the agents of a foreign power while on a massive steam-powered submarine. (Also included: mechanical squid.) Unlike, say, Cherie Priest of Gail Carriger, Mr. Green's work remains firmly ensconced in science fiction and, although certainly fantastic, never edges across into fantasy.

49. Lauren Beukes' Zoo City (2010). I'm not sure there's a safer pick as a contemporary SF "essential". Zoo City has all the makings of a future classic - using science fictional elements to prompt a discussion about apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa, class division, pop culture and even media savagery.

50. Lavie Tidhar's Osama (2011). More science fiction noir, beautifully written and astoundingly powerful. Osama doesn't try to make sense of a world that is, in many ways, senseless. But by incorporating science fictional elements, Mr. Tidhar's book gains the distance to talk about terrorism and 9/11 in a way that conventional literary fiction cannot.

...and that's fifty. What surprised you? What'd I miss? What shocking oversight should I be reading right now?

Don't forget, Ian's list is here and James' is here. And if you missed the first half of the list, you can find it here.

50 Essential Science Fiction Novels (Part 1: 1812 - 1979)

4. H.G. Wells' The Time Machine (1895). Mr. Wells is one of the few authors that could conceivably be on here multiple times, but with Tomkyns (above) covering off invasion scenarios, the choice is narrowed down pretty swiftly. The Time Machine uses a science fictional concept to talk about class (and the Morlock/Eloi trope has informed countless novels since then), has some fairly badass pulp adventure sequences and covers the "dying earth" scenario. This book should be essential for the harrowing final chapters alone.

3. Edward Abbott's Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions (1884). Probably should get this out of the way early - Flatland is the closest thing I'll have to "hard SF" anywhere on the list. Ostensibly a math text (and, in all fairness, a really good one), Flatland is also a brilliant social satire, lampooning the social rigidity, classism and misogyny of the time. Also, cool illustrations.

2. George Tomkyns' The Battle of Dorking (1871). One of the original "invasion literature" pieces, Mr. Tomkyns' short novel describes the invasion of a contemporary Britain by a militarily-superior Germany. It is the grandfather of many apocalyptic scenarios (as it begat Wells' The War of the Worlds) and alternate histories (as it begat through If It Had Happened Otherwise). The Battle of Dorking is also a great example of how science fiction is about the "now" and not the future. Inspired by the Franco-Prussian War, Dorking examines fears that the British may be complacent in their military and naval superiority, and the days of Empire could be on the decline...

1. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1812). This position works both chronologically and in terms of overall ranking. If there's a single, inarguable, essential work of science fiction, here it is. And what's not to love? Brilliant character development, twisty-turny plot, cutting-edge scientific ideas, moral ambiguity, even astounding, epic action. This one has it all.

Enough of the caveats, here are my first 25 picks, in chronological order. The remaining 25 will be posted tomorrow.

The term "essential" caused a bit of existential wibbling, but I finally decided on a rough sort of definition that these fifty books, as a set, had to paint some sort of picture of the best (the full spectrum of many bests) that science fiction can offer.

The last one is the nastiest of all, as I can't even fake it - this exercise has definitely exposed some fairly notable gaps (say... Samuel Delany, Joanna Russ, Diana Wynne Jones, Octavia Butler and anyone not Anglo-American) in my reading. Oops.

This list arose from a conversation with Ian Sales and J.P. Smythe. We all admired Abebooks' Essential Science Fiction list , but, as is human nature, found the list problematic in completely different ways. Being gentlemen, we decided to settle this the old-fashioned way - by scampering back to our various Internet hidey-holes and writing our own lists. ( Ian's is here ; James' is here .)

5. Charles Fort's The Book of the Damned (1919). Fortean 'science' and the concept of rigorously approaching unusual phenomena has informed a century of science fiction, up to and including the X-Files, the works of Warren Ellis and, arguably, the recent trend towards occult detection/police procedurals. It narrowly bumped Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World (1912) for this spot. Although The Lost World is a more enjoyable book, it is tough to compete with Fort's encyclopedic survey (and accompanying rationalisations), which encompasses everything from fairies to UFOs.

6. George Orwell's 1984 (1949). Another obvious selection. With a tip of the had to Yevgeny Zamyatin (We) and Aldous Huxley (Brave New World), Orwell's got this spot sewn up.

7. Robert Heinlein's The Man Who Sold the Moon (1951). I like Heinlein, and not just because he's got a soft spot for Kansas City. But Stranger in a Strange Land is gobbledegook, The Puppet Masters is silly and Starship Troopers is an argument for fascism. The Man Who Sold the Moon is a excellent example of mid-century American capitalist SF. Delos Harriman, the man obsessed with "owning" the moon is one of the most intriguing protagonists of the era - brains over brawn, ambition over scruples, and, ultimately, both endearing and tragic.

8. John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids (1951). As an aside, do you know how nuts this book sounds? "After a solar flare blinds the human race, predatory plants reign supreme." But Mr. Wyndham's 'cosy catastrophe' does so much right - it doesn't fuss with the science (swiftest, most hand-wavey apocalypse ever) and it focuses on an everyman. There's no epic quest to somehow (a bit late) 'save the day', The Stand, there's just the plodding, persistant maneuvering to survive.

9. Sarban's (John William Wall) The Sound of His Horn (1952). One of the great alternate history novels. A British POW who finds himself in a world where the Nazis won World War II and have established vast baronial estates across Europe. Utterly petrifying and beautifully written. Touches on eugenics, which is a nice SF touch, but that's an afterthought.

10. Leigh Brackett's The Sword of Rhiannon (1953). Sorry Mr. Burroughs, but Ms. Brackett did it better. Ms. Brackett's best space fantasy probably took place in her short stories, but The Sword of Rhiannon (originally The Sea-Kings of Mars, but her publishers thought readers were getting tired of Burroughs and wanted to hit a different audience) is still a brilliant book. It is easy to get bogged down in SF being "about" this and "about" that (it is the self-declared "literature of ideas" [shudder]) - but it is essential that we don't overlook the fun. And the adventures of archaeologist-renegade-thief Matthew Carse? Lots of fun.

11. J.T. McIntosh's One in Three Hundred (1954). A not-so-cosy catastrophe. The sun is growing, Earth is doomed. Humanity throws itself into a desperate effort to mass-produce spaceships and fling as much of the species as possible towards Mars. A grim little tale, made more so by McIntosh's dry telling of planet-wide torment. Also a fine example of reconstruction/terraforming SF. Nudged out Kim Stanley Robinson's Red Mars (1993) and Liu Cixin's The Wandering Earth (2000).

12. Richard Matheson's I am Legend (1954). The most uncosy catastrophe of them all? The last man on Earth (or is he?) ekes out a tormented existence in a world overrun by vampires. Again, an everyman catastrophe, rather than an epic battle for redemption. When Mr. Matheson does turn the plot towards a "quest", the ultimate conclusion is, even 50 years later, shocking. There are ten thousand science fiction novels emphasising Homo sapiens' assured predominance, this one does not.

13. Jack Finney's The Body Snatchers (1955). Possibly the second-best novel of science fiction horror ever written, a metaphor so compellingly written that it (ironically) addresses both Communism and McCarthyism and the progenitor of four different films. (Like The Day of the Triffids, this is another one that just sounds ridiculous as a one-liner: "Alien plants take our lives." What is it with plants?)

14. Frank Herbert's The Dragon in the Sea (1956). So here's a weird one. Were this list ten books, and not fifty, I'd slap Dune on it without thinking twice. It is a sprawling epic that touches every possible theme... but I'm not sure it is the essential volume for any of them. With the (relative) space allotted by having fifty books, The Dragon in the Sea is my pick. A claustrophobic tale, Dragon follows a submarine crew tasked with snaffling oil from the "East" in a post-peak oil world. Both as a picture of Cold War tension and a discussion of ecological consequences, this book is hard to beat.

15. Ray Bradbury's Dandelion Wine (1957). That's right. Over Farenheit 451 (1953). Superficially, Dandelion Wine is a wistful of a romantic era - apple pie Americana as painted by Norman Rockwell. But it doesn't take much reading to realise that this book is actually astoundingly heavy: a coming of age story about death, loss and the inexorable passage of time. The "Happiness Machine", one of the book's few overtly science-fictional elements reinforces these themes, a fragmented story about a futile attempt to distill 'joy' in the face of reality.

16. Macalypse the Younger and Lord Omar Khayyam Ravenhurst's Principia Discordia (1959). Like The Book of the Damned (above), the Principia's influence is too vast to ignore. Essentially the batshit Bible, it outlines the basic precepts of Discordianism: a conceptual religion based on the worship of chaos. The Principia both leads and epitomises two key trends in the science fiction of the era: a change in the epic narrative from Good vs Evil to Law vs. Chaos (later captured in the work of Michael Moorcock) and a subversive humour (later reflected in Kurt Vonnegut).

17. Philip Dick's The Man in the High Castle (1962) Probably the finest alternate history ever written, made more so by the fact that Mr. Dick's complicated triple-blind addresses the nature of history (and our understanding of it) itself. If that sounds ridiculously complex, it is... and yet still his most approachable work.

18. Madeline L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time (1962). If there's one sub-genre that gets short shrift on this list, it is science fiction intended for children or young adults. (Possibly because so much vintage SF is appropriate for all ages? Discuss.) Ms. L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time is a genuine classic, introducing four-dimensional travel to generations of young readers to this very day.

19. Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange (1962). For one, it still remains the best summary of the ethical arguments (both sides) around behaviour change. For another, it is linguistically brilliant - as carefully crafted as Tolkien's Elvish (but without a drop of pretension). And, for the third, potentially the greatest example ever of making a evil (or chaos, see above) empathic.

20. John Muller's (Lionel Fanthorpe) Survival Project (1966). Fanthorpe wrote over 180 science fiction books for Badger Books, 89 produced in a 3 year period alone (that's one every 12 days). I've not read all 180, but I'm pretty convinced that no great literature lurks in there. However, Mr. Fanthorpe is essential because he's the epitome of an era - quickly produced, character-devoid narratives based around thin (often absurd) ideas and whims. An era that shows no signs of coming to a close. It is fun to skate around the top of the glacier, but most science fiction is Fanthorpian.

21. Arthur C. Clarke & Stanley Kubrick's 2001 (1968). Most of Clarke's great stuff came in his short stories, and, as the book and the film were created simultaneously, it is easy to credit 2001 with influence across both media. Probably the best SF horror story (alluded to above), as well as an interesting (if vaguely incomprehensible) plot that simultaneously makes individual humans all-important while, as a species, renders us insignificant. Bonus points: putting HAL on here means I can ignore everything having to do with robots until this point. It (the impulse is to call HAL "he") not only wraps up all the Asimovian cyber-blah, but also moves it on, dare I say it, monolithically.

22. Ursula Le Guin's The Left Hand of Darkness (1969). Another author I'd rather have on here for short stories - The Compass Rose (1982) hits many of the same themes, but, in my eyes, more enjoyably. Still, this is about gender and understanding - I have sympathy to the argument that the book is becoming dated, and even more sympathy for the argument that its successor is sadly overdue.

23. Ira Levin's The Stepford Wives (1972). Oddly, Mr. Levin's one of the few authors that I would've liked to put on here twice - The Boys from Brazil is significant in the way it weaves science fiction into a contemporary thriller. But The Stepford Wives is the stronger of the two - a nice bit of horror, but an even nicer bit of social commentary in the way it describes the loss of agency that comes with adulthood, marriage, suburban living and just plain "being a woman in the 1970s".

24. J.G. Ballard's High Rise (1975). Pretty sure, of all fifty, this is the choice that'll prompt the most "WTF?". But, you know what, had it a drop of SFnal content, I would've put on Concrete Island instead (so ha). High Rise is social science fiction and, like Stepford, encapsulates the hopes and fears and aspirations and disappointments of a generation. (And, things being cyclical, I'm pretty sure High Rise is now relevant again.) Beyond that, it is one of the best dystopian novels ever written, made all the more compelling by the fact that it takes place in microcosm and in the here and now.

25. Douglas Adams' The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy (1979). Has there been a better or more thoughtful humorous SF novel? I don't extend the "essential" invitation to the rest of the series, which made the full metamorphosis from "funny" to "silly" to "deserves a spanking".

What'd I get wrong? What'd I get right? What egregious oversights need to be instantly corrected?

Don't forget to check out the other two lists as well: Ian Sales' and J.P. Smythe's. The second half of all our lists goes up tomorrow. Get those knives nice and sharp!

Powell’s Essential List: 25 Best Sci-Fi and Fantasy Books of the 21st Century (So Far)

Powell’s Essential List: 25 Best Sci-Fi and Fantasy Books of the 21st Century (So Far)

Let’s be honest: reality isn’t super appealing these days. So when we started to discuss this list and the titles we wanted to include, we really threw ourselves into that discussion. Which distant planets did we want to travel to? Which dragons did we want to battle? Which operatic space romances did we want to live vicariously through?

This is the list we compiled from those discussions, a list of books populated with mutants and robots and alien civilizations, prophets and thieves and shadows, mystics and inventors and space creatures. These are magical, larger-than-life books filled with mythology and adventure, galactic wars and history, science and philosophy, love and loss — books that aren’t afraid to explore issues of climate, race, gender identity, sexuality, and class, alongside much more intimate subjects, like heartache and hope.

Through the lens of this list, the future has as much potential to be bright as it does to be devastating.

The 21st century is only 22 years old (so far), but there have already been so many amazing science-fiction and fantasy books published. These are the 25 we consider essential.

— Powell's Books, 2022

buy now Perdido Street Station by China Miéville Sentient cacti, bird people, humanoid insects, artificial intelligence, dream-eating moths, demons, an interdimensional spider god, and a mob boss that looks like a cross between Hieronymus Bosch and Picasso paintings are just a handful of the vibrantly strange and mundanely horrific characters that populate this novel and the city of New Crobuzon, a steampunk fantasy police-state that took root in my mind from the moment I entered its borders and will stay with me forever. China Miéville is one of the leading forces in the genre of new weird fiction and this is arguably his magnum opus. The city feels so real that while reading it you may feel as if you're walking its grimy streets yourself. Just be sure you know where you're going, because all roads lead back to Perdido Street Station, and there is something hungry hiding in the rafters. – Ben T.

buy now American Gods by Neil Gaiman In 1992, Neil Gaiman moved to America. In 2001, he released American Gods. In the 10th anniversary edition, he recollects “this strange huge place where [he] now found [himself] living” and the urge not just to understand it but also to describe it. Describe it he did. I hesitate to use the term “masterwork” in book reviewing but here no lesser word applies. American Gods is masterful. Gaiman’s ability as a storyteller and myth weaver is on full display, covering everything from folklore, mythology, immigration, globalization, capitalism, and tragedy (both cosmic and personal). It’s the story of one man, of a nation, of the land, of a small icy town, promise, lies, and gods (both old and new). If you haven’t read it, I am so, so, so excited for you. – Sarah R.

buy now Pattern Recognition by William Gibson Set in the then-present day of 2002, William Gibson’s Pattern Recognition is the work of a mind that is usually thinking ahead, but has paused to look deeply at the present. Reading it today, it’s remarkable how — although it may no longer be about the present — it remains shockingly current. Gibson foresaw — any write-up of a William Gibson novel will contain at least one sentence starting this way — that information merchants would have outsized power in the 21st century. In Pattern Recognition, a consultant (who is literally allergic to bad logos) is hired by an incredibly well-resourced ad firm to find the creator of a mysterious viral video. Although political and medical disinformation aren’t a centerpiece of this book, it’s clear reading it today that all the necessary pieces were in place and discernable two decades ago, if you knew where to look. And William Gibson has always known where to look. – Keith M.

buy now Mistborn by Brandon Sanderson Skaa-born teen and street thief Vin is in over her head. Posing as a noblewoman as part of a scheme to steal precious atium requires that Vin amplify her newly discovered powers of Allomancy to influence the nobility and also learn to fight assassins for her own survival. Power gained from this world’s magic, based on internally burning various paired metals, has long been used to assault and murder defenseless skaa workers; now society is ripe for a revolution. But Mistborn isn’t just a fun, fast-paced heist novel with surprising plot twists. Brandon Sanderson presents a fascinating dystopian world of ash and mistwraiths, enslavement and giftedness, with deep insight into the nature of charisma, the need for hope, and the lengths to which people will go for both revenge and freedom. – Sara F.

buy now The Lies of Locke Lamora by Scott Lynch The Lies of Locke Lamora is a sparkling gem of a book — dialogue, plot, tone, characters — so seamlessly and artfully written that the reader can happily and completely escape into the world Lynch has created. Locke Lamora is a master thief, part of the Gentlemen Bastards, a group of con artists who enjoy relieving the wealthy citizens of Camorr from the crushing burden of their wealth. Filled with twisty plot turns and a setting reminiscent of late medieval Venice, this is well worth savoring. – MaryJo S.

buy now The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu The Three Body Problem is hard sci-fi — the kind of hard sci-fi that will leave you puzzling over astrophysics and researching the particulars of quantum mechanics for days — but the patient reader will be rewarded with a dazzling epic full of mystery and moral dilemma. Liu grapples with the darkness of humanity, but leaves room for hope that someday we will fling ourselves out into space, into a vast life that only visionary sci-fi authors can currently imagine. – Emily B.

buy now The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss The Name of the Wind is the story of Kvothe, who grows up in a nomadic troupe of players, the Edema Ruh, where he learns the fundamentals of magic, music, and the dramatic arts. After years as a penniless orphan in Tarbean, he eventually attends the University, where he narrowly avoids expulsion several times. Kvothe is brilliant, full of panache and daring, but certainly not exempt from suffering or heartbreak. The genius of The Name of the Wind is that the skill of the author elevates it beyond the sum of its highly entertaining parts. Long fantasy novels with magical schools are plentiful, but The Name of the Wind casts a spell that has not diminished with the passage of time. – MaryJo S.

buy now The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi This story hits the ground running through the dangerous winding streets of a future Bangkok, walled against the rising sea and populated with characters clawing out existence amidst food shortage and energy collapse. One of the single greatest science fiction settings I have every had the pleasure of “visiting.” Calories have become currency, crops are going extinct, and synthetic lifeforms are on the brink (or past the point) of singularity. The Windup Girl is thrilling, a little terrifying, and steps more toward reality every year. I will never stop telling people to read this book. As I’ve told everyone I’ve ever recommended this to, come find me when you get to the end of chapter 49. – Sarah R.

buy now Saga: Volume 1 by Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples It’s hard to argue with the assertion that Saga is the best graphic series of the last decade — just look at the pile of awards it has amassed. The magic of this book is in the incredible alchemy that comes from the creative partnership of writer Brian K. Vaughan and illustrator Fiona Staples. Together, they take an eclectic blend of sci-fi and fantasy tropes mixed with piercingly authentic emotions and then combine them with incredible design and flawless plotting. The first volume of Saga is sure to get you hooked. Lucky for you, there’s many more volumes in this sprawling epic that still has yet to reach its conclusion. – Keith M.

buy now Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie Before there was Murderbot, there was Breq, the AI protagonist of Leckie’s Ancillary Justice, which caused a genderfuss when it was first published in 2013. Breq is non-gendered and the default pronoun for much of society in that civilization is “she,” regardless of gender. Four years later, All Systems Red, the first Murderbot novella, was published. In the space of four years, awareness of gender fluidity expanded. – MaryJo S.

buy now Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer I simply cannot say enough good things about Annihilation and the Area X trilogy.This is not just an amazing story; for me, it is an obsession. I loved the first book in the series, Annihilation, and anxiously awaited the follow-up books. This book is haunting in its imagery, and VanderMeer packs a lot into such a small book. I felt bonded to the anonymous Biologist in a way that I have not felt with other protagonists. Perhaps it is my own scientific background and deep love for wild nature that had me following this story as if it could be my own, but I really think it’s Vandermeer’s unique style of writing that makes this story truly special. – Angela G.

buy now The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers If you like a healthy dose of hope with your science fiction, there’s no better place to start than with Becky Chambers. The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet gives us the gift of a found-family ragtag crew of adventurers, genuinely fascinating alien races, and super cool technology (their spaceship runs on algae!). This book, and the rest of the Wayfarers series, builds its foundation on character-driven kindness: that a better, more-hopeful universe can exist if we reach for the people closest to us and choose gentleness over bitterness again and again. Fans of Firefly and Star Trek, reach for this read next! – Anna B.

buy now Binti: The Complete Trilogy by Nnedi Okorafor Binti runs away from her beloved desert home and family on Earth to go to the most prestigious university in the galaxy. She starts her journey as an outlier, as the first-ever Himba to be accepted. Mid-way, her ship is attacked and she witnesses a horrific massacre — and has to come up with a way to survive and broker peace between two warring groups before the ship lands. The experience colors Binti’s life, world, and sense of self in innumerable ways throughout the collected novellas. There’s so much to love about Binti, but I’m struck most by how Nnedi Okorafor maintains a clear voice for our heroine while she is changed by and changes everyone she comes across and while she works through the ongoing trauma of the ship massacre and discovers secrets about her home and family. An unforgettable coming-of-age story, a realistic and fantastical look at intergalactic space treaties, and a bombastic slice of life that may make you regret letting your mathematical education lapse. It’s perfect. – Michelle C.

buy now Seveneves by Neal Stephenson Neal Stephenson’s books seem to either have devoted fans or vocal detractors, and Seveneves is perhaps the most polarizing book I’ve ever read! I have always enjoyed books that break the conventions of storytelling, and while I was initially shocked at where Stephenson takes Seveneves two-thirds of the way through the novel, I quickly found myself happily along for the ride. Seveneves explores what humanity will do when the moon inexplicably breaks apart, eventually hurtling life on earth towards a global extinction event. The goal is to convert the ISS into an Ark and create a new beginning for the human race. Seveneves embraces Stephenson’s signature deep dives into a lot of (very cool) science. But it is also an epic nail-biter of a tale with great characters that you will root for with every fiber of your being. – Lesley A.

buy now The Fifth Season by N. K. Jemisin The Fifth Season brings about devastation, volcanos erupting, the ground beneath your feet falling apart — communities don’t survive it; it’s a complete reset of the world they know. We follow the perspectives of Damaya, Syenite, and Essun — three women coming to terms with their connection to the Earth, their control of the plates, and how to best manipulate this energy for the protection of civilization and their own safety. Jemisin flawlessly executes this multiple perspective narrative in a richly imagined and immersive dystopian setting. The magic system is also well developed and wonderfully scientific and offers something new and refreshing to the genre. This is a story that will draw you in immediately from the sheer depth and richness of the world. Featuring an amazing, diverse cast of fully realized characters and intricate plot lines that beautifully interweave with each other, this thorough and expansive story is a perfect blend of high fantasy and dystopian speculative science fiction. Complex, imaginative, and absolutely brilliant. – Tawney E.

buy now Uprooted by Naomi Novik Uprooted by Naomi Novik is one of those stories that you feel has somehow always existed. I mean that as a highest compliment. It captures the essence of a classic fairy-tale: what is really in that tower? and just how dangerous are those woods exactly? Novik has proven time and time again that she’s a fantasy collection must-have with napoleonic dragons, magic schools, fable, and more. Still, Uprooted is where I always send people first. Its magic system is unique and wonderful, the romance steamy and believable, the friendship powerful, the world dark and dangerous but still beautiful. I’m going to go read it again. – Sarah R.

buy now All the Birds in the Sky by Charlie Jane Anders Charlie Jane Anders’s All the Birds in the Sky is a carefully crafted story with a clear narrative and a robust set of themes and metanarratives running parallel to it, just below the surface. The novel follows Patricia, a young girl who learns that she will become a powerful witch, and Laurence, a boy with an incredible aptitude for technology. Neither child is popular at school or well-supported by their parents. They find each other and form a fast friendship, until they learn that they are prophesied to become bitter enemies and avatars of incompatible worldviews. If Patricia and Laurence sound like familiar types to readers of sci-fi and fantasy, they should! But as Anders is playing with tropes, she’s also interrogating what it means to become an adult and when and how we should put away childish things. – Keith M.

buy now All Systems Red by Martha Wells With a title like Murderbot Diaries, you might expect Martha Wells’s award-winning series to be about a ruthless killing machine. What you get instead is a moody, slightly sarcastic security unit who just wants to be left alone to watch all the entertainment feeds it’s downloaded. But as weird things start to glitch, Murderbot’s newest mission of keeping a scientific team from getting themselves killed while on planet might just teach it a few things about human interactions and even lead to the development of some gooey “emotions” (whatever those are). This is the first in the series and it is highly addictive — nine out of ten people will suffer major withdrawals while waiting on more to be released. Murderbot has quickly become one of my go-to comfort reads. #Murderbot4ever – Mecca A.

buy now The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden Vasya is the heroine of my 13-year-old (and, let's face it, 31-year-old) inner horse-girl-talking-to-magical-creatures dreams. In this first installment of the Winternight Trilogy, Vasya grows from an untamed girl to a fiercely independent free-spirit, who embraces the traditions passed down through the women in her family. When her classically evil step-mother appears, she brings with her new beliefs that threaten to wipe out the old ways and free an ancient evil. Set in a snowy and magical forest landscape in 14th century Russia, you'll want to settle in with a hot cup of tea for this cozy read, even in the summer months. – Corinna K.

buy now On a Sunbeam by Tillie Walden When I first read On a Sunbeam, a graphic novel about a girl who travels across the universe to find lost love and a space crew that restores crumbling, alien architecture, it was with that wide-eyed, hungry wonder you always chase as a reader. It’s an expansive, beautiful book, with carefully rendered characters that are as intricate and lovely as Tillie Walden’s illustrations of distant planets and cathedral-like ruins. On a Sunbeam contains so much: it’s a queer coming-of-age story, a story about salvaging (love, relationships, former civilizations), a love letter to found family, a romance, a space opera, and... the list could go on. This book is lush and generous and big and gracious. I am so grateful to Walden for bringing it into the world. – Kelsey F.

buy now Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James This National Book Award finalist starts with a failure — Tracker, a man with an uncommonly good nose, is telling the story of how he ended up in this jail cell, about the boy he was meant to find, about how he came to have the eye of a wolf. Black Leopard, Red Wolf unspools in spirals, and we learn more about how he came to this quest (and the ragtag rogue’s gallery that he uneasily agreed to work with), when he first met the leopard who can turn into a man, what monsters he has known and slain. Marlon James has created a fantasy epic for the ages, a twisting, betrayal-studded, magic-imbued adventure that mesmerizes even when the violence on the page gets especially gruesome. I would not pick this up if you’re looking for a light book; I insist you read it if you're looking for an unforgettable tale that will rearrange your thoughts and blow your hair back. – Michelle C.

buy now Exhalation by Ted Chiang For over 30 years, Seattleite Ted Chiang has slowly and steadily been writing emotionally intelligent, speculative short stories. He’s not a quick writer, or a prolific one. He’s published just 18 stories in that time. But what incredible stories they are. (Sci-Fi award committees agree: Chiang’s won four Hugos and four Nebulas.) Exhalation is Chiang’s second collection, and though it was only published a few years ago, these nine stories have become classics of the genre, exploring the complicated relationships between humans and machines, determinism and free will. I can’t wait to read what he writes next, though I will try to be patient. – Adam P.

buy now The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon In this quasi-medieval world, East and West are at odds — the East reveres their water dragons and their dragon riders, while the West hates all dragons after one of the wretched, fire-breathing ones nearly destroyed the world. There’s a large cast of endearing characters, but the hearts of the story are Ead, lady-in-waiting to the queen, and Tané, dragon-rider in training, both harboring dangerous secrets. The Priory of the Orange Tree harkens back to the best of classic fantasy. It’s both epic in scale and scope — spanning decades and continents — yet still manages to remain intimate. While long, the pacing doesn’t lag, with big doses of adventure and unapologetically queer romances. – Carly J.

buy now The Empress of Salt and Fortune by Nghi Vo This slim volume is the introduction to Nghi Vo’s Singing Hills Cycle, and an entryway to a lush and complicated world. The series follows Chih, a travelling cleric who records histories from the people they talk to on their journeys. Lore is delivered in bits and pieces — each snippet of a story is a rich delicacy, leaving the reader with just the right amount of knowledge and mystery. The Empress of Salt and Fortune, in particular, packs an emotional punch with its story of political intrigue, love, loss, and revenge. By playing with myth, oral tradition, and the slippery nature of history, Vo crafts a wistful atmosphere. The result is a kind of gentle and nostalgic magic for the reader to sink into, as if into a delightful dream. – Marley S.

buy now A Master of Djinn by P. Djèlí Clark A Master of Djinn returns us back to P. Djèlí Clark’s alt-Cairo historical steampunk universe that he first introduced us to in The Haunting of Tram Car 015 and A Dead Djinn in Cairo. Dapper-dressing Agent Fatma el-Sha’arawi — along with her quasi-girlfriend — are joined this time with both new and old colleagues from the Ministry of Alchemy, Enchantments, and Supernatural Entities. It’s another case full of murders and magical mischief, mysterious Djinn, fallen angels, and maybe a few old Egyptian Gods. I had so much fun immersing myself in this world and hope there will be more to come.– Mecca A.

Also by Powell's Staff

• 50 Books for 50 Years

• 25 Women to Read Before You Die

• 25 Books to Read Before You Die: World Edition

• 25 Memoirs to Read Before You Die

• 25 Books to Read Before You Die: 21st Century

• 25 Books to Read Before You Die: Pacific Northwest Edition

Write a Comment