20 Best Science Fiction Books Of The Decade

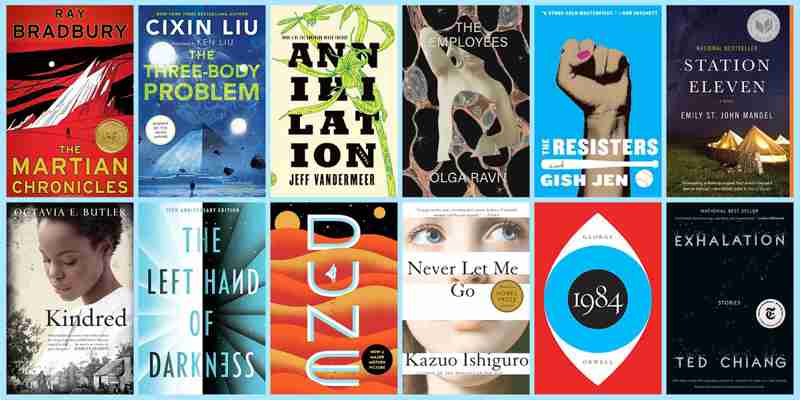

The 50 Best Sci-Fi Books of All Time

Since time immemorial, mankind has been looking up at the stars and dreaming, but it was only centuries ago that we started turning those dreams into fiction. And what remarkable dreams they are—dreams of distant worlds, unearthly creatures, parallel universes, artificial intelligence, and so much more. Today, we call those dreams science fiction.

Science fiction’s earliest inklings began in the mid-1600s, when Johannes Kepler and Francis Godwin wrote pioneering stories about voyages to the moon. Some scholars argue that science fiction as we now understand it was truly born in 1818, when Mary Shelley published Frankenstein, the first novel of its kind whose events are explained by science, not mysticism or miracles. Now, two centuries later, sci-fi is a sprawling and lucrative multimedia genre with countless sub-genres, such as dystopian fiction, post-apocalyptic fiction, and climate fiction, just to name a few. It’s also remarkably porous, allowing for some overlap with genres like fantasy and horror.

Sci-fi brings out the best in our imaginations and evokes a sense of wonder, but it also inspires a spirit of questioning. Through the enduring themes of sci-fi, we can examine the zeitgeist’s cultural context and ethical questions. Our favorite works in the genre make good on this promise, meditating on everything from identity to oppression to morality. As the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Doris Lessing said, "Science fiction is some of the best social fiction of our time.”

Choosing the fifty best science fiction books of all time wasn’t easy, so to get the job done, we had to establish some guardrails. Though we assessed single installments as representatives of their series, we limited the list to one book per author. We also emphasized books that brought something new and innovative to the genre; to borrow a great sci-fi turn of phrase, books that “boldly go where no one has gone before.”

Now, in ranked order, here are the best science fiction books of all time.

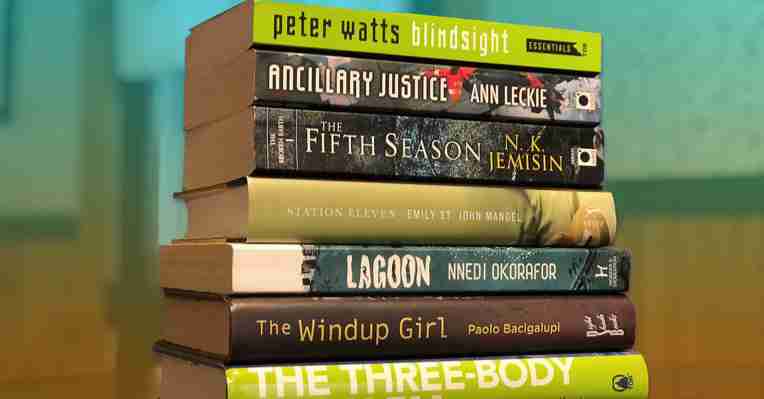

15 recent sci-fi books that forever shaped the genre

What does the future hold? In our new series “Imagining the Next Future,” Polygon explores the new era of science fiction — in movies, books, TV, games, and beyond — to see how storytellers and innovators are imagining the next 10, 20, 50, or 100 years during a moment of extreme uncertainty. Follow along as we deep dive into the great unknown.

Science fiction is in a constant state of flux, and coming up with a solidified canon is something that will vary from person to person. Certainly, there are classics throughout the genre, books that stand far apart from their peers, like Frank Herbert’s Dune, Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, or Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness. These books are legendary not only for providing readers with much to think about, but also impacting the writers that follow them, influencing subject matter, technique, perspective.

The last 15 years have provided plenty of fodder for science fiction authors, and looking back, it’s clear that science fiction is in a period of transition: there are more people writing stories than ever before, from every type of background and on a variety of new platforms that didn’t exist before. And amidst that transition, there have been plenty of novels that have broken through and changed how science fiction looks.

The following 14 books are some of the most consequential and groundbreaking stories that have hit bookstores or bookshelves in that time: books that forever altered the genre in a number of ways by changing the conventions or tropes that authors traditionally used, blazed forward a path or popularized some new thing, or which have proven to be wildly popular with readers around the world.

Blindsight by Peter Watts (2006)

First contact between humanity and an extraterrestrial civilization are a cornerstone of science fiction, ranging from aliens with funny noses to the genuinely alien. Peter Watts’ novel Blindsight stars after the planet is bombarded by a strange cluster of objects that release a single broadcast before going dark. When scientists receive another transmission from a comet outside of the solar system, they dispatch an expedition composed of five trans-human specialists, including a vampire.

What they discover is indeed alien: a sort of hive-mind intelligence that’s part of a much larger diaspora. Where many science fiction adventures deal with humanity’s introduction to a galactic civilization in which we become an equal partner/citizen, Watts posits something far stranger: interstellar intelligence that’s genuinely alien, and to which humanity is providing to be a major nuisance and threat. It’s a groundbreaking novel that helped break authors away from human analogs and into more stranger, introspective territory about our place in the cosmos.

Related books: The Dark Forest by Cixin Liu, Story of Your Life by Ted Chiang, Embassytown by China Mieville

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins (2008)

Adult and YA science fiction are often marketed to very different audiences, with both sides looking down on the other. It’s a nonsensical barrier, and Suzanne Collins’ book The Hunger Games is a good demonstration that the YA designation doesn’t necessarily mean that an author is talking down to its audience.

Set in a dystopic future where the United States has collapsed and been replaced with Panem, children are selected for a brutal competition every ten years from each of the country’s twelve districts, in which they fight to the death, as punishment for a failed revolution.

Collins’ book deals with pressing issues of brutality and trauma, as well as wealth inequality, poverty, and revolution. With its release in 2008, the book became a major bestseller and media franchise, and unleashed a floodgate of dystopian-themed YA novels that explored the darker parts of modern society.

Related books: Ship Breaker by Paolo Bacigalupi, The Maze Runner by James Dashner, Divergent by Veronica Roth

The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi (2009)

Between major hurricanes, widespread wildfires, and a global temperature that keeps rising, climate change is at the forefront of the public’s consciousness in the last decade. While the issue was certainly settled in 2009, Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl was a breakthrough for science fiction by putting a world with a drastically changed climate front and center.

Set in a world where oil is no longer a thing and where mega agricorps control the world’s food supply with genetically modified crops, Bacigalupi’s story is set in a futuristic Thailand that’s managed to stave off environmental apocalypse: because the country has been able to keep outsiders out, it’s avoided crop failures and famine. That success however, comes with problems: Agents from some of those agricorps are working to get their hands on the country’s seedbank to solve some of their problems, while a genetically-modified woman tries to escape sexual slavery as war looms.

Climate change is a subject that’s ripe for fiction, but Bacigalupi goes beyond mere disaster porn with this novel. The Windup Girl looks at how rampant capitalism and its associated abuses underpins the climate disaster.

Related books: Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins, New York 2140 by Kim Stanley Robinson

The Red trilogy, Linda Nagata

Robotics and science fiction are synonymous (2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the term), and over the years, we’ve seen authors approach the field ranging from benevolent servants (C-3P0 or Robbie from Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot), to cooly malevolent (Hal, from 2001: A Space Odyssey.)

As robotics and artificial intelligence has advanced in recent years, so too have the stories that we’ve told about them. One of the most intriguing reads about artificial intelligence is Linda Nagata’s The Red, a military thriller set in the near future. The story follows Lieutenant James Shelley, a soldier who’s part of a cybernetically enhanced unit, and who has a knack for getting out of trouble thanks to a voice in his head.

That voice turns out to be a massive, distributed artificial intelligence that’s emerged amidst the world’s myriad of systems, and it uses soldiers like Shelley to carry out its plans, particularly when it comes to imminent threats to human civilization, like nuclear warheads. Nagata’s vision for artificial intelligence is scary and realistic — a powerful, unknowable force that has the potential to shape our lives in ways that we don’t expect, and it’s a very different take on the types of robots and artificial intelligences that have come before it.

Related books: Autonomous by Annalee Newitz, Sourdough by Robin Sloan, Burn-In by August Cole / P.W. Singer, The Lifecycle of Software Objects by Ted Chiang

Leviathan Wakes by James S.A. Corey (2011)

When Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck — writing jointly as James S.A. Corey — began a new space-opera novel, friends advised them to focus on epic fantasy instead. Space opera, they were told, just didn’t sell. They ignored the advice, aiming for “beer and pizza money,” and ended up with a novel that blended hard science fiction and noir mystery as the specter of war looms over the solar system.

Leviathan Wakes kicks off Corey’s The Expanse series, a sprawling, ambitious project that explores humanity’s future in space, looking not only at the dangers of balkanization and marginalization in society, alongside the dangerous and perilous possibilities that a galactic diaspora might pose to humanity when we venture out into the stars.

While space opera never really went away, Leviathan Wakes has helped revitalize the story, paving the way for other authors to explore space and uncover new revelations about humanity as they do so.

Related books: Embers of War by Gareth Powell, Murderbot series by Martha Wells

The Martian by Andy Weir (2011)

Andy Weir’s The Martian has what is probably the luckiest of origin stories. Weir worked as a programmer for a number of software companies over the course of his early career, but had always written on the side, publishing short stories like The Egg on his website in 2009. That same year, he began writing a story about a stranded astronaut on Mars, in which he worked out how a realistic mission to Mars would play out.

That realism is one reason why The Martian grabbed a lot of people’s attention: Weir paid a considerable amount of time getting the details right for a realistic mission to Mars, and the steps that his hapless astronaut, Mark Watney needed to take to survive, from how he grew his food, how he figured out how to communicate with Earth, and ultimately escape from the planet.

Additionally, The Martian helped demonstrate the potential of self-publishing. When Weir wasn’t able to sell the novel to a publisher, he began serializing it on his website for free, and then began selling it on Amazon. The book quickly became a bestseller, which led to a major publishing deal and then a blockbuster movie directed by Ridley Scott.

Related books: Ready Player One by Ernest Cline, Wool by Hugh Howey, Terms of Enlistment by Marko Kloos

Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie (2013)

When Ann Leckie burst onto the science fiction with her debut novel Ancillary Justice, it attracted immediate praise and criticism for one of her stylistic choices: a civilization that didn’t utilize conventional pronouns.

In the very distant future, the Radchaai Galactic Empire rules over countless civilizations with the help of powerful starship AIs, loaded with corpse soldiers that it controls like puppets. One shipmind, the Justice of Toren, is destroyed, but who survives in the mind of one remaining soldier, and who sets off to extract revenge for her destruction.

Leckie helped popularize two things: she developed a civilization that broke completely away from the conventional depictions of gender and identify. She certainly wasn’t the first to use these tropes, but following the book, science fiction authors have been increasingly freer to explore an increasingly sophisticated field of gender identity and depiction.

Ancillary Justice also explored another heady issue: looking at the nature a galactic empire not through the lens of building a uniform interstellar civilization, but through that of imperialism, colonization, and subjectification.

Related books: A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine, The City in the Middle of the Night by Charlie Jane Anders

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers (2014)

Ever since cyberpunk and Frank Miller’s run on Batman in the 1980s, it feels like the entire field of science fiction has lurched somewhat towards an aesthetic of grim realism. The world is a dark, angry place, one where terrible things happen and life is meaningless. There’s no shortage of genuinely insightful, good books that adopt that mindset, such as Richard K. Morgan’s Altered Carbon or Paolo Bacigalupi’s relentlessly bleak The Windup Girl or The Water Knife. And that’s before you get to the superhero films (at least up until Guardians of the Galaxy or Thor: Ragnarok).

That’s why Becky Chambers’ debut novel The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet was such a breath of fresh air for a lot of readers. It’s an endlessly optimistic science fiction adventure that follows a young woman, Rosemary Harper, who joins the crew of a ship that helps create wormhole tunnels, The Wayfarer, as they travel across the galaxy, stopping by planet after planet.

It’s a cozy read, one that will feel familiar to anyone who likes the Firefly brand of space opera, in which Chambers takes a keen interest in understanding the interpersonal workings of each of the crew members and how they fit together. It’s a book that’s endlessly fascinated about how a complicated world works, and one that retains its sense of optimism when its characters take to the stars. It’s a book that understands that communities and civilization as a whole operates because of a greater sense of empathy, understanding, and compassion for one’s neighbors, a lesson that’s desperately needed these days.

Related books: Closed and Common Orbit / Record of a Spaceborn Few by Becky Chambers, Space Opera by Catherynne Valente

The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu (2014)

Liu Cixin’s novel The Three-Body Problem and sequels (The Dark Forest and Death’s End) are ambitious books that have a sense of classic 1970s bigness to them, but which also explore humanity’s place in the cosmos. The series follows humanity’s discovery of an extraterrestrial civilization out there, and the subsequent invasion of Earth, starting during the Chinese Cultural revolution and stretching all the way to the heat death of the universe. Along the way, Liu explores how dangerous life in the larger universe could be, muses about dystopias and technological utopias, throws in some massive space battles, and just about everything else you can think of.

The incredible success of The Three-Body Problem (President Barack Obama and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg have praised the book) has led to more visibility for the larger science fiction scene in China, leading to the publication of more of Liu’s books, but others as well, like Hao Jingfang’s Vagabonds, as well as dozens of shorter works from the country that have been translated into English in the years since.

This success in Chinese science fiction has morphed into additional interest in science fiction from around the world, and an increased awareness that science fiction isn’t just a North American/European style of storytelling: it’s truly global.

Related books: Ball Lightning, Liu Cixin, Vagabonds by Hao Jingfang

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (2014)

For much of its history, literary critics and creators have often looked at science fiction like some unidentifiable splotch you might find under your shoe, something that’s beneath the dignity of serious readers and thinkers. Nevermind that science fiction has a long track record of books that are easily on par with their “literary” counterparts.

Despite those long-standing prejudices, the conventions and tropes of science fiction have begun to bleed into conventional literary circles, especially as those authors are beginning to grapple with a world that increasingly looks like the setting of a science fiction novel. One stellar example of this is Emily St. John Mandel’s novel Station Eleven, which explores the aftermath of a deadly flu pandemic that devastates civilization, and in which the survivors band together to not only try and rebuild society, but try and preserve the things that make life worth living, like art and theater.

Mandel’s novel attracted considerable attention from both genre and literary readers, and it felt very much like a novel that helped convince readers of both stripes that (a) neither were going anywhere, and that (b) there are elements from both traditions that are well worth digging into.

Related books: Severance by Ling Ma, Machines Like Me by Ian McEwan, Famous Men Who Never Lived by K. Chess

Lagoon by Nnedi Okorafor (2014)

Nnedi Okorafor’s response to Neill Blomkamp’s film District 9 was one of anger, because of the film’s portrayal of Nigerians and the misuse of its African setting. Her response was to write her own take on an alien invasion set in Africa, Lagoon.

With the work, Okorafor has embarked on a specific subgenre of science fiction that she calls “Africanfuturism” — something she notes is different from the more widely known Afrofuturism. It, she says, is a mode of fiction that is Africa-centric, rather than science fiction generated from within the African American community, and “more directly rooted in African culture, history, mythology and point-of-view as it then branches into the Black Diaspora, and it does not privilege or center the West.”

It’s an important distinction, one that highlights the increasingly global nature of the genre. As the world has become more connected, creators from all over the world are beginning to utilize the tropes of science fiction to imagine futures without that western mindset.

Related books: Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James, Binti by Nnedi Okorafor

The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin (2015)

N.K. Jemisin’s vision of Earth is one that’s pummeled by “fifth seasons”, periodic, apocalyptic events that sends the remnants of humanity fleeing into strongholds to try and wait out the worst disasters. Jemisin follows a woman with powers (called an orogen) named Essun as she works to survive amidst a system that routinely oppresses people like her, and as she works to remake the world to become a better place.

The Fifth Season is the work of a writer at the top of her game: Jemisin splits the story’s perspective not only between three individuals, but with three different tenses, all coming together at the end for an excellent reveal.

While the novel is stylistically phenomenal, it’s what Jemisin does with her story that sets it far apart from its peers, grappling with an important question: how do you take a world that’s intrinsically broken, and make it better. A recent panel discussion at New York Comic Con discussed the nature of fantasy literature, with several creators pointing out that the genre has traditionally upheld established power structures. Jemisin pushes against that trope, using her characters to break down traditional norms and rebuild a world that’s more fair, just, and equal.

Related books: The Poppy War by R.F. Kuang, The Stars are Legion by Kameron Hurley

Aurora by Kim Stanley Robinson (2015)

How do you travel between stars if you’re writing a story set in a realistic world where things like hyperspace and warp drives can’t exist? You hitch a ride on a generation ship, a massive vessel that is designed to be a small world unto itself, allowing multiple generations of humans to survive on the long voyage in the depths of space.

Kim Stanley Robinson turns his eye towards what a generation ship might look like, following the passengers of a generation ship bound for Tau Ceti. Robinson is known for his deeply-researched works, and Aurora presents one of the best-realized depictions of what life out beyond our solar system might look like. The generation ship is approaching the end of its journey, and it’s in tough shape: it’s running low on some critical elements and when it arrives at Tau Ceti, its passengers discover that while their new home can technically support human life, it will be an inhospitable existence for generations to come. With this book, Robinson highlights an inconvenient truth about the galaxy and science fiction: humanity is a species that’s specifically suited for living on Earth, and that its health and well-being is paramount for our survival and future.

Related books: Children of Time by Adrian Tchaikovsky, Seveneves by Neal Stephenson, Luna: New Moon by Ian McDonald

The Calculating Stars by Mary Robinette Kowal (2018)

In Mary Robinette Kowal’s alternate history, an asteroid comes down off the coast of Washington D.C., a potential doomsday event that devastates the world just after World War II. Governments around the world come to the conclusion that if it wants to survive, humanity must establish off-world colonies on the Moon, Mars, and beyond, and sets up a multinational space program to achieve that goal. Think JFK’s speech on steroids.

Kowal draws on the present state of space exploration for this alternate history, putting some of its darkest moments front and center, where women and people of color were denied admission into the space program because of systemic racism and sexism. Her characters fight to be part of the program, arguing that if humanity wants to survive, everyone has to come along, including women and people of color.

In doing so, Kowal tackles head on some of the deepest assumptions that we’ve held about the space program, and shows how systemic inequality has impacted our progress in space. While we’ve been able to solve the technical barriers to get into orbit, in order to survive and thrive, we’ll need to solve some of those more intractable problems.

Related books: The Future of Another Timeline by Annalee Newitz, Wayfarer series by Becky Chambers

The Lesson by Cadwell Turnbull (2019)

A spacecraft comes to land over not New York City or another major world capital, but over the U.S. Virgin Islands. First contact with aliens known as the Ynaa proves to be fraught: they’re benevolent, but can be extremely violent. When a young boy is brutally killed after what seems like a minor slight, it sets into motion a series of actions that could unravel relations between the Ynaa and humanity.

While reading this book, I couldn’t help but think back on the state of race relations in the United States: at its heart, it’s about young, Black men who run into the unmovable and unwavering force that is the US law enforcement mechanism. The book is a study in power and how two opposing sides warily regard one another, and what happens when things get out of control.

Given the events of the summer of 2020, this is a theme that’s undoubtedly here to stay as authors use science fiction to explore this deadly power dynamic and white supremacy that’s part of American life.

Related books: The Deep by Rivers Solomon, The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin, Riot Baby by Tochi Onyebuchi

20 Best Science Fiction Books Of The Decade

After much mulling and culling, we've come up with our list of the twenty best books of the decade. The list is weighted towards science fiction, but does have healthy doses of fantasy and horror. And a few surprises.

This list is alphabetical, and not in order of awesomeness. All are equally great and worthy of your attention. In deciding which would make the list and which wouldn't, we weighed not only our opinions, but also those of the critical community at large - looking at how each book was received by reviewers for mainstream publications as well as science fiction magazines. There were many, many books we love that almost made the cut - if we'd let ourselves go it would have been more like the 100 best books of the decade.

Also, all of the books on this list were originally published in English. Regrettably I'm not conversant enough in global science fiction to make an educated "best of" list that includes works written in other languages. I hope those of you who are will add your picks to the comments below.

Advertisement

Acacia: The War with the Mein, by David Anthony Durham (Doubleday)

According to the Washington Post:

From the first pages of Acacia, Durham, a respected historical novelist, demonstrates that he is a master of the fantasy epic. He quickly sets out in broad strokes the corrupt world that these unwitting children have been raised to rule. For 22 generations, the Akarans have presided over the empire of Acacia. And for 22 generations, they've sent a yearly shipment of child slaves to mysterious traders beyond their borders, "with no questions asked, no conditions imposed on what they did with them, and no possibility that the children would ever see Acacia again." In exchange, the Akarans get "mist," a drug that guarantees their subjects' "labor and submission." . . . Durham sacrifices nothing — not psychological acuity, not political complexity, not lyrical phrases — as he drives the plot of this gripping book forward. The names of people and places sound as if they've been recalled from a dusty past, not cobbled from J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle Earth, a far too common practice among fantasy writers. Tropes that sound outlandish — "dream-travel," for one — are credible in Durham's telling. And the story always surprises. Characters that seem poised to take center stage are killed abruptly. Evil often triumphs.

G/O Media may get a commission Deal! 60% Off the First Four Months of Audible Premium Plus Kick back and unwind with an audiobook.

Unwind with 12 credits to spend on any audiobook, and free access to the Premium Plus selections, no credits needed. Subscribe at Amazon Advertisement

This is the first novel in Durham's planned Acacian Trilogy. The second novel, The Other Lands, has recently been published and the third is on the way.

Advertisement

Air, Or Have Not Have, by Geoff Ryman (Gollancz)

Air won the Clarke Award and was nominated for a Nebula. Here is what Strange Horizons' Geneva Melzack had to say about it:

Chung Mae lives in Kizuldah, a tiny mountain village in the country of Karzistan. The people in Kizuldah live traditional sorts of lives, making a living through farming and migrant manual labour. TV has barely arrived in the village when a national test of Air, a new form of virtual media technology, takes place, badly shaking up Kizuldah's traditional existence. The person most shaken up is Chung Mae herself, who is involved in an accident in the midst of the test that fuses her, in the virtual world of Air, with her elderly neighbour Old Mrs Tung, killing Mrs Tung in the process. Air tells the story of how Chung Mae learns to adapt to her new situation, and the work she has to do to help the rest of her village similarly adapt to the changes that the test has wrought and the further changes that she knows will come when Air is fully implemented in a year's time . . . It might be tempting to read Air as a book that is advocating change and the embracing of the new, but there's more to it than that. Change in Air is simply something that happens. It is inevitable. The future is not necessarily any better than the past, but it is coming nevertheless.

Advertisement

The Alchemy of Stone, by Ekaterina Sedia (Prime)

Here is what io9 had to say about this book when it came out last year:

With a face made of porcelain, a wind-up heart, and a talent for alchemy, Mattie is hardly a typical science fictional robot. While most novels about robots focus on how these humanoid machines are stronger and smarter than humans, Ekaterina Sedia's The Alchemy of Stone explores the vulnerability of mechanical beings who depend on humans for repairs and survival. Mattie is a rare emancipated automaton in an industrial city hovering on the edge of a workers' revolution. She's gone against the wishes of her Mechanic creator and joined the ranks of the biochemist-mystic Alchemists, selling medicines and perfumes to the city's middle class. Sedia's novel captures the surreal strangeness of a city whose power structure is about to be toppled, and her focus on Mattie's relationship with her creator allows her to grapple with the tiny power struggles inherent in all human relationships - especially those between men and women.

Advertisement

The Baroque Cycle, by Neal Stephenson (HarperCollins)

Love it or hate it, you have to admit that Stephenson's mammoth historical science series changed the way we think about science fiction - and managed to blow away both science fiction fans and the masses who made these novels bestsellers. Like Cryptnomicon, the Baroque Cycle blends the facts of science history with intense, intellectually-challenging adventures that make you feel smarter even when you whoop, "Dude, that was awesome!" It's a retelling of the revolutions in science and rationality during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Of the first novel in the series, the New York Times says:

Given the apparent depth of Stephenson's research, it seems clear that the anachronisms with which he seeds the novel are deliberate. Some are playful, as when a guard throws Daniel a letter with the words, ''You've got mail,'' or when the 17th-century Venetians succumb to ''Canal Rage'': ''They insist that gondoliers never used to scream at each other in this way. To them it is a symptom of the excessively rapid pace of change in the modern world, and they make an analogy to poisoning by quicksilver, which has turned so many alchemists into shaky, irritable lunatics.''

Advertisement

Confessions of Max Tivoli, by Andrew Sean Greer (Picador)

Very likely the true inspiration for the recent film The Case of Benjamin Button, this bestselling novel explores the life of Max Tivoli, a man who is growing younger - and his relationship with the woman he loves. Bookslut describes the novel like this:

With nothing known about his medical condition and no name for what he is, Max can only look to the few historical instances of cases similar to his — a pair of twins born in France as well as the son of a Viennese merchant. These bits of "research" lend a credibility to the story, making this fictional memoir seem all the more based on a factual account. Greer writes this story as if it were nonfiction — the actual diary of a man who wishes only to have his unique story known. "I burst into the world," he writes, "as if from the other end of life, and the days since then have been ones of physical reversion, of erasing the wrinkles in my hair, bringing younger muscle to my arms and dew to my skin, growing tall and then shrinking into the hairless, harmless boy who scrawls this pale confession." These are Max's experiences, regrets, and lost hopes, once found in a dusty, old attic — the efforts of an old man caught in a young boy's body, committing his life to literature.

Advertisement

Down And Out In the Magic Kingdom, by Cory Doctorow (Tor)

Doctorow burst into the mainstream with this hit novel about warring factions in Disneyland: Those who are trying to preserve the ancient amusement park from being made virtual, and those who are happy to see it digitized. It was also, famously, the novel where Doctorow invented the term "whuffie," a term that refers to cultural capital - or, as South Park would later put it, "internet dollars." As Nisi Shawl said in the Seattle Times:

Even when science fiction is based on solid predictions, it can demonstrate the pinwheeling pyrotechnics of a first-class fireworks display. A longtime observer of life online, Doctorow depicts a cashless economy based on the constant, automatic tracking of public reputations by a nameless online utility. Referred to as "The Bitchun Society" (a la President Lyndon Johnson's "Great Society"), the dominant lifestyle confers immortality (of a sort) on all participants. All one has to do is periodically record one's brain patterns — to be imprinted on force-grown clones in the event of an unwanted death. (No charge for this service; there's no charge for anything, as long as one maintains a high enough reputation.) It's that trick that allows hero Jules to investigate his own murder.

Advertisement

The Execution Channel, by Ken MacLeod (Tor)

One of the superlative MacLeod's most critically-acclaimed and internationally popular novels, it's the tale of a near-future anti-terrorist dystopia. Known for his complicated political writing, MacLeod spun a tale that captured the public's interest, and the attention of political subcultures, too.. The Socialist Review said of the book:

More spy thriller than science fiction, The Execution Channel is full of the paranoia and the obsessive zealotry of security services in a world where power struggles between states obscure all else. The story centres on James Travis, an IT engineer. His daughter, Roisin, is part of the anti-war movement, and his son, Alec, is in the army. Despite taking neither position, Travis is headhunted for French intelligence, ostensibly due to having made the statement: "I just hate the Yanks." When a nuclear explosion destroys a US controlled airbase in Scotland Roisin is witness to it as part of a peace camp outside. . . The Travis family and US conspiracy theorist and blogger Mark Dark [try] to make sense of the events amid lies and disinformation.

Advertisement

Glasshouse, by Charles Stross (Ace)

Stross produced a lot of great fiction in the 2000s, but Glasshouse, a novel about far-future gaming, espionage, war, and masculinity, was a standout. io9 chose it as one of the "science fiction novels that can change your life," and we said:

Stross has said he had the Stanford prison experiments in mind when he wrote this far-future tale of drifters who sign up for a "glasshouse" experiment to recreate the twentieth century in an isolated space habitat. They'll be arbitrarily assigned genders, and forced to engage in certain kinds of conformist behaviors for points. Our heroes, ill-at-ease in the genders they've been given, figure out that there's a deeper plot at work and must try to outsmart the glasshouse prison game while fighting mind viruses that can reorganize your whole consciousness. With unexpected twists and turns, this book is the very best mindfuck you've ever had.

Advertisement

Harry Potter Series, by JK Rowling (Bloomsbury)

Like Durham's Acacia series, the Harry Potter books challenged conventional wisdom about what should happen in a fantasy series. At the same time, Rowling helped revive traditional fantasy storytelling for millions of people across the world. And she gave grownups permission to love young adult writing again. Of the Harry Potter series, Entertainment Weekly's Tina Jordan says:

I'm amazed, when I sit back, at the sheer, immensely complicated arc of the story; Rowling has always said she had the entire seven-book series plotted out from the very beginning, and it's clear she did. I'm stunned at the way she managed to tie up so many of the plot strands, even while weaving in new ones (and while introducing new characters too, albeit no one very important). Having just reread the first six books, I now realize how many small clues were strewn throughout (and how few I managed to pick up). Yet despite the complicated plots and subplots, despite the effortless allusions to mythology and classic tales . . . Rowling winds up her tale with a stunningly beautiful simplicity.

Advertisement

Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell, by Susanna Clarke (Bloomsbury)

Another fantasy writer who completely transformed the genre in the past decade is Clarke, whose Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell is both a literary classic and a gorgeous, smart take on the thorny relationship between the kingdoms of Europe and the kingdom of Faerie. The Washington Post reviewed the bestseller like this:

[Clarke's] antiquarian romance ... resembles Umberto Eco's Foucault's Pendulum, Lawrence Norfolk's Lempriere's Dictionary and John Crowley's Aegypt sequence — deeply learned novels that reimagine the nature of history. For Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell is at heart a book about the present's relationship to the past. In its pages Clarke takes the accepted fabric of English culture and inserts just a single new thread: that during the Renaissance, magic actually worked. Alas, the actual ability to perform magic gradually faded away, even as the centuries-long reign of the powerful magician-sovereign of the North — John Uskglass, the Raven King — passed into the popular mind as a lost golden age.

Advertisement

Look to Windward, by Iain M. Banks (Orbit)

Look to Windward is a novel of galactic war and personal loss, human revenge and AI regret. It's also one of the most moving, intelligent novels in Banks' legendary Culture series. The UK Guardian describes the premise of the novel:

Eight centuries after the Culture fought off its greatest challenge, a war that raged for 50 years and destroyed entire solar systems, the glow from one of the exploding stars has just reached [the orbital world] Masaq'. "Tonight," as one visitor puts it, "you dance by the light of ancient mistakes." And now another chicken is coming home to roost. Billions have died because of the Culture's meddling in the neighbouring civilisation of Chel, where it set off a civil war, and some of the Chelgrians have decided to take revenge. Their instrument is a soldier called Quilan, who is sent to Masaq' on a mission that is a mystery even to him. He is one of the misguided yet decent villains who are a feature of these tales: complicit in a planned "gigadeathcrime", he is still honourable and courageous. As the moment of reckoning approaches, his memories take us back to the days before the war, when his existence still had meaning and his wife was alive.

Advertisement

The Mount, by Carol Emshwiller (Small Beer Press)

Poetic and intense, The Mount is a deceptively simple story about humans revolting against a group of alien conquerers who love humanity - as pets they can ride on. Here's what io9 said about it:

Carol Emshwiller's quiet, disturbing novel The Mount is about what happens when small alien invaders called Hoots take over the planet and begin breeding humans for transportation. Hoots have weak legs that fit perfectly around human necks, as well as superior weapons that easily convert the disobedient to dust. What's compelling about this beautifully-written novel, though, is that it's no simple "aliens oppress humans" tale. It explores what happens when humans get used to, and even enjoy, their servitude.

Advertisement

Oryx and Crake, by Margaret Atwood (Anchor)

A controversial story of virus apocalypse caused by corporate biotech run amok, this novel dazzled mainstream readers with its persuasive vision of the near-future. It was also a strong entry in science fiction's biopunk subgenre, a cautionary tale of what happens to so-called progress when piloted by greed. Said the New York Times:

Atwood's scenario gains great power and relevance from our current scientific preoccupation with bioengineering, cloning, tissue regeneration and agricultural hybrids, and she strikes a note of warning as unambiguous as Mary Shelley's in ''Frankenstein.'' This is the intention of the novel: to goad us to thought by making us screen in the mind a powerful vision of competence run amok. What Atwood could not have intended, and what is no less alarming and exponentially more urgent, is the resonance between her rampaging plague scenario and the recent global outbreak of SARS. Moving from book to newspaper, or newspaper to book, the reader realizes, with a jolt, how the threshold of difference has been lowered in recent months. The force of Atwood's imagining grows in direct proportion to our rising anxiety level. And so does the importance of her implicit caution.

Advertisement

Pattern Recognition, by William Gibson (Putnam)

Gibson reinvented himself in the 2000s as a writer of technothrillers that feel like science fiction despite being set in the present - or, in the case of Pattern Recognition, one year before the book's publication. An enthralling mix of Gibson's favorite obsessions - branding, computer technologies, and artisanal smuggling networks - the book is also a moving portrait of the emotional ties forged between fans of an obscure set of viral videos online. In Wired, Rudy Rucker wrote:

What Gibson gives us is an international spy thriller comparable to the slightly skewed tales of Jonathan Franzen or David Foster Wallace. His story's central McGuffin is a fragmentary, workstation-rendered romance movie known simply as The Footage. It consists of 100-odd supernally beautiful snippets of video that someone has anonymously posted on the Web. A rabid online cult has grown around the flick, and a Belgian advertising exec (with the improbable name of Hubertus Bigend) hires Cayce Pollard to find the maker. Bigend's goal: Tap into The Footage's primo street cred strategy for profit . . . Gibson pulls you in with big ideas that make solid material for word-of-mouth proselytizing. But Pattern Recognition's essential quality is the sensual pleasure of its language. Gibson has a knack for choosing - or coining - the right phrase. With a poet's touch, he tiles words into wonderful mosaics. An expressway is "Blade Runnered by half a century of use and pollution." The Tokyo skyline is "a floating jumble of electric Lego, studded with odd shapes you somehow wouldn't see elsewhere, as if you'd need special Tokyo add-ons to build this at home."

Advertisement

Perdido Street Station, by China Miéville (Del Rey)

The first of Miéville's stunning New Crobuzon novels, Perdido Street Station is a tour-de-force of worldbuilding and complicated, character-driven drama. Strange Horizons described the book like this:

New Crobuzon is full of alienated individuals, social groups, and species; Miéville's main characters live on the margins of society, either by choice, or social pressure, or both. Identities are fluid, allegiances shift suddenly; spies and moles infest the city and its underworld. Betrayal is commonplace, and trust is at a premium. The main character, Isaac Dan der Grimnebulin, embodies this tension. (Isaac — the sacrificial son? Isaac Newton? Both?) A marginalized scientist pursuing his own quixotic line of research — the "crisis engine" — he is also socially outcast by virtue of his romantic relationship with a xenian, a khepri artist named Lin. The khepri are partly insectile, partly anthropoid, and Lin, too, is an outcast from her society — an alienated artist who has broken away from her brood in pursuit of a more individualized art. Isaac and Lin's relationship leaves them vulnerable to blackmail and manipulation, and makes their lives in an already hazardous society even more precarious. The book's action begins with the appearance of yet another marginal, outcast character, a garuda (avian-derived) named Yagharek, who has been stripped of his wings by his species as punishment for crime; he commissions Isaac to help him regain his ability to fly. In the course of his research Isaac inadvertently unleashes. . . well, something Not At All Nice . . . The theme of the meaning and nature of consciousness, sentience, and rationality underlies the frantic action in the malevolent city. . . Perdido Street Station is an impressively imaginative novel from a promising new writer.

Advertisement

Rainbows End, by Vernor Vinge (Tor)

A masterpiece of plausible futuristic technologies, Rainbows End is also a very personal story of a man who has recovered from Alzheimers - only to discover that his once-magnificent mind is now healthy but average. At the UK Guardian, Wendy Grossman wrote:

Set in 2025, the characters are surrounded by logical extensions of today's developing technology. Wearable computing is commonplace. Tagging and ubiquitous networked sensors mean you can look at the landscape with your choice of overlay and detail. People send each other silent messages and Google for information within conversations with participants who may be physically present or might be remote projections. One character's projection is hijacked and becomes the front for three people. The owner of another remote intelligence is unknown. Several continents' top intelligence operatives try to solve a smart biological attack that infects a test population with the willingness to obey orders. Vinge makes two opening assumptions: no grand physical disaster occurs, and today's computing and communications trends continue.

Advertisement

Stories of Your Life And Others, by Ted Chiang (Orb)

Chiang is one of the legends of the science fiction world, often hailed as the best short story writer of his generation. With a keen interest in science, and a healthy love for magic, Chiang writes stories that are both gorgeous and profound. SFSite enthuses:

Stories of Your Life and Others abounds with examples of why Ted Chiang's stories have continued to be award winners. From "Understand", which both plays homage to and expands upon Daniel Keyes' classic "Flowers For Algernon" to "Story Of Your Life," in which a linguist confronts the relationship between language and reality, it will not take readers new to these stories very long to appreciate their quality and beauty. Science fiction has always depended on writers who work best at shorter lengths to continue to examine new ideas and push the boundaries of the field. In the decade plus a few years since he first started publishing, Ted Chiang has shown himself to be more than up to that task.

Advertisement

Time Traveler's Wife, by Audrey Niffenegger (MacAdam/Cage Books)

Critically-acclaimed, and this year released as a feature film, this is the tale of a man who suffers from a rare time-traveling condition. The question Niffenegger asks is how such a man could ever have a meaningful relationship, when he's constantly uprooted from the present and propelled to different eras. USA Today said:

Niffenegger, despite her moving, razor-edged prose, doesn't claim to be a romantic. She writes with the unflinching yet detached clarity of a war correspondent standing at the sidelines of an unfolding battle. She possesses a historian's eye for contextual detail. This is no romantic idyll. The ability to revisit one's past doesn't necessarily illuminate one's understanding of events. And knowing the future is not particularly a good thing, Niffenegger's story implies. This is what makes her story both compelling and unsettling. Time traveler Henry is limited in his capacity to change himself, let alone past or future events. His freakish condition brings Clare into his life, but it also keeps them from being resolutely happy; he never knows when he will disappear, and she never knows when - or in what shape - he'll return.

Advertisement

Tooth and Claw, by Jo Walton (Tor)

Winner of the World Fantasy Award, Tooth and Claw is an alternative history masterpiece from an author acclaimed for her facility with narrative time-tweaking. Satirical and scathing by turns, Tooth and Claw is a nineteenth century novel of manners in which dragons are the dominant species on Earth. Here's what io9 said about it:

Influenced by Victorian writer Anthony Trollope, Tooth And Claw is about the fate of two sisters whose father dies before they are married off. They cannot inherit his caverns, and he's left them almost no money. One goes to live with their married sister, whose husband is a cruel land owner who eats the children of his servants. The other goes to live with their brother, a pastor and new husband who lives in the caves of a very wealthy woman whose son takes a shine to her. Walton manages to translate Victorian details into dragon life, commenting on what is fashionable in cave decoration and describing the dangerous machinations of dragon bureaucrats. There's even a Middlemarch-esque subplot where one of the sisters gets involved with a movement to better the lives of the poor. And of course it's a romance – even dragons get a happy ending. The best part about Tooth And Claw is that it isn't just a simple parody. Certainly it is very witty, but it is also a fascinating thought experiment in which the most savage creatures of our imagination turn out to be the very best society that 19th century civilization has to offer.

Advertisement

World War Z, by Max Brooks (Crown)

A gamechanger in the horror/scifi world that hit just as the zombie craze was reaching manic intensity, Brooks' novel is written in a disturbing, satirical documentary style. The Onion AV Club said:

Write a Comment